A shiny red metal heart stands erect in the garden at Oslo Cathedral in the city centre.

Bold letters spell out the words in Norwegian, followed by the English translation: Greatest of all is love. Even for a tourist like myself, a translation is almost unnecessary; just the sight of the heart and the accompanying faces of those lost to July 22’s terrorist attack in 2011 is enough to render all words powerless against the tsunami of grief that is guaranteed to gush from anyone who encounters it.

A memorial to those who lost their lives on Utoya (photo by Mitchell Jordan)

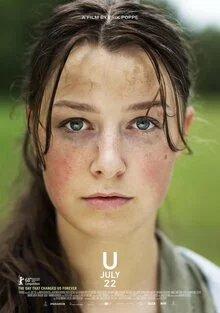

Much has been written about the attack — referred to by most Norwegians simply as July 22 — and now we have award-winning director Erik Poppe’s latest film U – July 22 revisiting it. Shot in real time in one single take, the 90-minute drama retraces the tragedy that took place first in the city centre, then on Utøya island, just outside of Oslo, through the eyes of the (fictitious) Kaja (Andrea Berntzen), a teenage girl who is part of the Labor Party’s summer camp.

Admittedly, I wrestled with the idea of watching this film. Norway has always been a country dear to my heart, in part because of the overwhelming kindness of its people, so to partake in something so voyeuristic seemed insensitive. I’m not sure what it was that made me give in. Probably the fact that I’d written about it previously, and a few years had passed by now.

Not that this made the experience any less raw. U — July 22 is a film which begins at the end. We learn what happens through text on a black screen the second it starts and yet, deceptively enough, we soon realise that in fact we know nothing.

That’s because no matter what you have read or watched about the attacks before, nothing compares to hearing the first gun shot, the first scream, watching youths flee through a forest that, under any other circumstances, would be idyllic.

Within 20 minutes, I fought the urge to walk out. I felt trapped; I wanted to know that I could escape; but I couldn’t bring myself to turn my back on the 100-plus people on Utøya, many of them teens, knowing what was going to happen.

For all the almost unbelievable horror that happened on Utøya, Poppe’s film is one of immense subtlety. He goes to great lengths not to give the attacker the disproportionate attention he received in the media by never once naming him, and out of both respect and agreement this review will do the same. The closest we ever get to seeing him is a black figure firing a gun. Of course there will be those who criticise such an omission, yet in doing this Poppe conveys something far more powerful: a deadly shadow who, from afar, may appear human but is capable of the most inhumane acts possible.

Instead, we meet many of the victims through Kaja, who is on a desperate search for her sister, Emelie, who she’d spent the morning arguing with. With Kaja on the run, we never stay in the one spot for long or learn what happens to most of the terrified teenagers she encounters.

Instead, we meet many of the victims through Kaja, who is on a desperate search for her sister, Emelie, who she’d spent the morning arguing with. With Kaja on the run, we never stay in the one spot for long or learn what happens to most of the terrified teenagers she encounters.

Much of the film is punctuated by gun shots (it’s believed the attacker fired over 100 times in total), yet every shot reverberates just as much as the first. There are flashes of corpses, and at least two death scenes, but Poppe balances this with close-ups of mosquitoes biting the flesh, hands gripping hold of mud and branches in the forest, using symbolism to show what we already know. If only other cinema could show such restraint.

U — July 22 finishes with the sound of water (cleansing? continuance?) and the timely message that the right-wing sentiment which fuelled Norway’s greatest tragedy since World War 2, not only still exists today, but is growing.

As a cinema-goer, my pet hate is people who talk, or munch popcorn, throughout the film. Can’t you handle 90 minutes of silence? I feel like snapping. This time, I barely battered an eyelid when the couple sitting behind me sighed or gasped throughout the senseless slaughter. In fact, I was grateful for the distraction. It reminded me that I wasn’t on Utøya.

Leave a Reply